There is a country wide debate on why Pakistan should not build more dams? Pakistan has long been told that dams are the ultimate solution to its water and power crisis. Mega-projects like Mangla Dam, Tarbela Dam and Neelum–Jhelum Hydropower Project were hailed as saviors of agriculture and energy. Yet, the country still faces crippling water scarcity, floods and expensive electricity. Today, experts argue that Pakistan should not build more dams. Instead, the focus must shift to solar energy, renewable solutions, and sustainable water management (Tribune, PakistanToday).

Why Pakistan’s Water Crisis Cannot Be Solved with More Dams

The 20th-century development model was based on the idea that humans could “conquer nature” with engineering and technology (Scott, James C., 1998). Governments dammed rivers, blasted mountains and borrowed billions from global institutions.

Rivers are not pipelines, they are living ecosystems that evolved over millions of years (Alla Khosrovyan, 2024). Stopping their flow disrupts aquifers, wetlands, and agriculture (Yanfeng et al., 2021). In fact, a river that does not flow is no longer a river.

Globally, countries have moved away from mega-dams (TheEconomicTimes). Initiatives like “Room for the River” in Europe and “Rewilding Projects” show that giving rivers space is more effective than choking them with concrete walls.

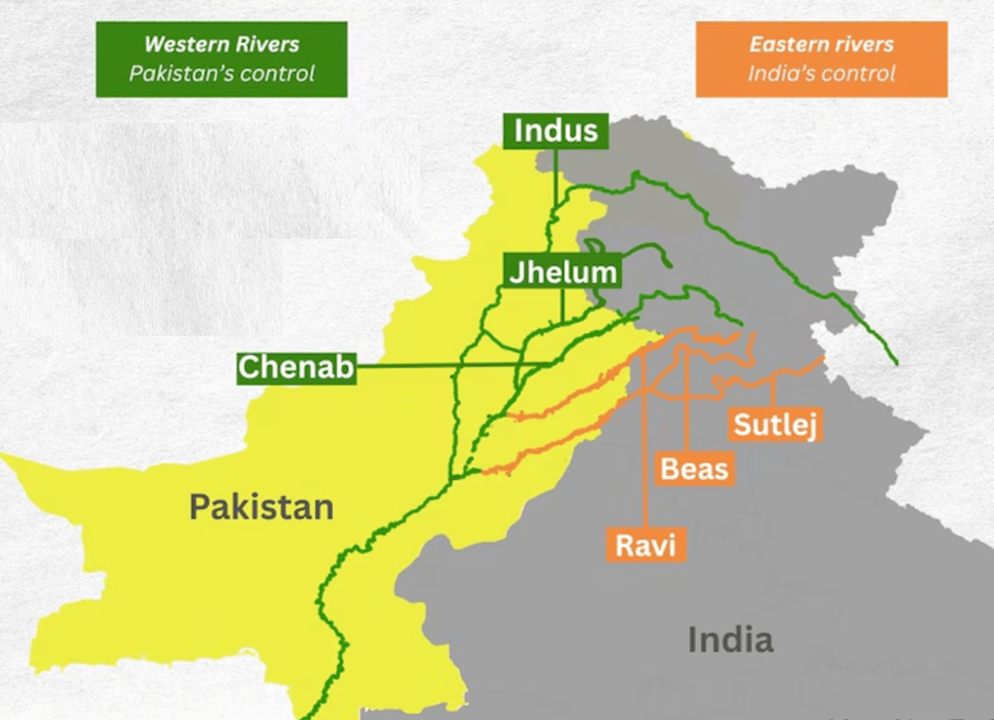

The Indus Waters Treaty: Pakistan’s Hidden Surrender

The Indus Waters Treaty of 1960 is often celebrated as a diplomatic success. In reality, it was one of the greatest hydrological humiliations for Pakistan.

- Pakistan surrendered control of three eastern rivers (Ravi, Beas, Sutlej) (WorldBankGroup).

- India was legally allowed to discharge untreated industrial waste into rivers flowing downstream into Pakistan [Article III(10) in the copy of the Indus Waters Treaty].

- Pakistan was lured with promises of Mangla and Tarbela Dams, locking it into a cycle of debt and dependency (Tribune).

This treaty forced Pakistan to accept dirty water in exchange for clean water, poisoning farmland and communities for generations.

Economic Imperialism and the Debt Trap of Hydropower

After World War II, global powers used financial institutions like the World Bank and IMF to push mega-projects in newly independent countries (InternationalRivers). In Pakistan, dams became tools of economic imperialism.

Projects such as the Neelum–Jhelum Hydropower Project were sold as sources of “cheap electricity.” Instead, they became debt-ridden disasters:

- Billions of dollars borrowed (DAWN).

- Frequent shutdowns due to tunnel collapses in seismic zones (TheNews).

- Hidden surcharges on citizens’ electricity bills (DAWN).

- Electricity produced at some of the highest costs in Pakistan (DAWN).

Instead of solving the energy crisis, these dams deepened Pakistan’s financial crisis.

Environmental and Social Costs of Building More Dams in Pakistan

Dams do not only create debt; they also bring long-term environmental and social damage:

- Displacement: Entire communities lose homes and agricultural land.

- Siltation: Reservoirs lose capacity within decades.

- Seismic risks: Many dams sit on active fault lines.

- Pollution: Under the Indus Waters Treaty, Pakistan receives toxic drain water.

- Health impacts: Contaminated rivers cause widespread disease.

The Neelum–Jhelum project, built in one of the most seismically active regions, has already shown structural failures. Instead of providing cheap hydropower, it has become a burden on the economy and public health.

Solar Energy vs Hydropower: Why Pakistan Should Not Build More Dams

Pakistan is ideally located in one of the sunniest zones in the world, with many regions receiving 2,300-2,700 hours of sunshine annually and 5-7 kWh/m²/day solar irradiance (Haleema et al., 2016). Engineers install solar panels much faster than they build large dams, and the panels require less maintenance while causing far less environmental disruption.

With this natural advantage, Pakistan could meet its entire energy demand from solar while avoiding debt, displacement and ecological destruction. Yet, outdated policies and vested interests keep the country stuck in a hydropower illusion.

Rethinking Pakistan’s Energy and Water Future

If Pakistan wants to break free from its water crisis and energy debt, it must shift away from dams and embrace 21st-century solutions:

1. Invest in solar and wind energy. It is cleaner, cheaper and faster to build.

2. Adopt nature-based solutions like “Room for the River” to manage floods.

3. Renegotiate unfair clauses of the Indus Waters Treaty.

4. Educate policymakers and citizens to move beyond the outdated “dam mindset.”

5. Protect rivers by considering them as living ecosystems and not through concrete storage tanks.

Conclusion

Dams are not Pakistan’s salvation. They are symbols of debt, ecological destruction and outdated development models. The future lies in solar energy, renewable power and letting rivers flow naturally.

With its platinum-level solar potential and rich river systems, Pakistan has the tools to secure a sustainable water and energy future, if it chooses the path of science and sustainability over concrete and debt.

That’s exactly why Pakistan should not build more dams.

FAQs

Q1: Why do experts argue that Pakistan should not build more dams?

A: It is because of the fact that dams create long-term debt, ecological damage and displacement, while failing to solve Pakistan’s water and energy challenges. Renewable options like solar and wind are cheaper, faster and more sustainable.

Q2: Are dams completely useless for Pakistan?

A: No, existing dams contribute to hydropower and irrigation, but building new mega-dams in seismic zones with high debt costs is risky and unsustainable.

Q3: What are the alternatives to dams for Pakistan’s water and energy security?

A: Investing in solar and wind energy, improving water conservation, rethinking the Indus Waters Treaty and adopting nature-based flood management like “Room for the River.”

Share Your Thoughts

What do you think — should Pakistan keep investing in mega-dams or pivot fully toward solar and renewables? Share your thoughts in the comments — your perspective could be part of the solution.